Coming from a family with service on the railways dating back to the London, Midland & Scottish Railway (LMS) and possibly even to the London & North Western Railway (LNWR), I could not resist including a chapter on railway history, with particular reference to Scotland and the Glasgow area.

Railways, in the form of waggonways, existed long before the advent of steam locomotion and were built primarily to transport stone from quarries, and coal from mines. Barrows set on wheels were moved around on wooden rails mounted on logs or on blocks of stone. In due course, the rails were topped with a strip of iron and eventually fully cast iron rails were introduced, providing even greater strength. The early iron rails were flanged but later the flanging was incorporated into the wheel design and this is still the case today. Motive power for the early waggonways was provided by man, mule or the force of gravity, whichever was appropriate. One of the earliest waggonways in Scotland was built in 1722 at Tranent in East Lothian and used to transport coal from the pits there to the small port of Cockenzie on the Firth of Forth. In between Tranent and Cockenzie were the salt pans of Prestonpans, a name familiar to many Scots as it was the site of a famous victory by the army of the Young Pretender over the Government forces led by Sir John Cope in 1745.

A quantum leap in the evolution of the railways was the harnessing of steam power for the purpose of locomotion. The earliest application of this new power source was in pumping water from mines and Thomas Newcomen developed the Atmospheric Engine for this purpose in 1712, so named because it operated at or very close to atmospheric pressure. The engine worked by using a movable piston to raise and lower a rocking beam, which in turn operated a lift pump. The efficiency of Newcomen’s steam engine was greatly improved by James Watt who was working on the maintenance of scientific instruments at Glasgow University. In the course of repairing a model of Newcomen’s engine, he realized that a significant amount of energy was being wasted by repeatedly heating and cooling the cylinder. Watt’s incorporation of a second condenser into the design in 1765 not only significantly improved the efficiency of the steam engine, it was the breakthrough that spurred the Industrial Revolution.

The portrait of James Watt (1736–1819) painted by Carl Frederik von Breda

The next step in the development of the railways was the application of steam power to self-propulsion and it was Richard Trevithick, a mining engineer from Cornwall, who built the world’s first working railway steam locomotive. Trevithick was very familiar with the pump engines used in Cornish mines and he was also greatly influenced by his neighbour William Murdoch who had developed a model steam carriage. Improvements in boiler technology enabled steam engines to operate at higher pressures, which were essential to provide the power needed to haul heavy loads. On 21 February, 1804, Richard Trevithick’s locomotive hauled the world’s first steam train on the tramway of the Pen-y-Darren ironworks in South Wales.

A recurrent problem in running these early trains was the continual breakage of the cast iron rails which proved to be very brittle under the weight of the heavy steam locomotives. One of the people working on this problem was George Stephenson, a Northumbrian, who not only improved rail strength and durability but also achieved fame as a locomotive designer and builder of railways. Together with his son Robert, he surveyed the land for the construction of the Stockton & Darlington Railway in 1821. The railway opened on 27 September 1825, when the steam locomotive “Locomotion”, built by Stevenson’s company and driven by him, hauled an 80-ton load of coal and flour nine miles in two hours. Also attached to the train was a passenger carriage called “Experiment” carrying dignitaries and so the Stockton & Darlington Railway became the first inter-city railway in the world to convey passengers in a train hauled by a steam locomotive.

The first railway in Scotland to be authorized by an Act of Parliament was the Kilmarnock & Troon Railway, which was built to facilitate the transport of coal from the Ayrshire pits to the coast. The railway opened from St. Marnock’s Depot, Kilmarnock to Troon Harbour on 6th July, 1812 and was a essentially an upgraded waggonway, having cast iron rails and being double-tracked throughout. The rails were flanged and sunk into the ground. For the first five years, haulage was provided by horses, and then a steam locomotive built for colliery work at Killingworth was brought in and this became the first steam locomotive to run in Scotland. Unfortunately, its heavy weight caused frequent breakages to the cast-iron rails so it only served for a trial period.

Before the railways really took hold, the prime means of transporting coal in bulk to growing cities and their industries was by canal. It was this increasing demand for coal that drove Scotland into the canal age. There were coalfields to the east of Glasgow in the Monklands, an area that included the Burghs of Airdrie and Coatbridge. Construction of the Monkland Canal began in 1770 and the final section leading into the Townhead Basin was completed in 1794. An even greater enterprise, the Forth & Clyde Canal, was begun in 1768 and completed in 1790, connecting the East and West Coasts. However, Edinburgh was still left out, so in order to provide a link, the Union Canal was built between 1818 and 1822, connecting Falkirk on the Forth & Clyde Canal with the capital city. Now, Glasgow and Edinburgh were linked by waterways and Monkland coal could be supplied to the capital in bulk. The problem was that the route was highly convoluted. Coal barges would initially have to travel west from the pits at Calderbank and then negotiate the basins at Townhead and Port Dundas in Glasgow before reaching the Forth & Clyde Canal whereupon they would begin their journey eastward. It would take about a week just to reach Kirkintilloch which was still to the west of the Monklands. To overcome this problem, a direct railway connection was proposed between the coalfield and Kirkintilloch, and on 17 May, 1824 an Act was passed authorizing the construction of the Monkland & Kirkintilloch Railway.

This was the first railway in the Kingdom to obtain an Act authorizing the use of steam locomotives from the very beginning. ( The Act establishing the Stockton & Darlington Railway had specified horse-haulage and it was subsequently amended to permit steam-haulage. ) The Monkland & Kirkintilloch Railway would provide a more direct route for the transport of Monkland coal to Edinburgh and an alternative means for its transport to Glasgow, in both cases overcoming the monopoly of the Monkland Canal.

The railway was also perfectly situated for the transport of minerals. Blackband ironstone containing 35% iron and rich in coal had been discovered in the Monklands in 1801. James Beaumont Neilson subsequently showed that the process of iron smelting could be greatly improved if you preheated the air supplied to the blast furnace, a process he patented in 1828. Now the Monklands would become an international centre for iron smelting and the resourcefulness of the ironmasters led to a proliferation of railways in the region.

To be continued.

Climbing Cowlairs Bank

This famous photograph by Dr. Tice F. Budden shows a “double-headed” North British Railway (NBR) express climbing Cowlairs Bank around 1900. There is a rope attached to the leading locomotive and, until banking engines were introduced, the ascent out of Queen Street Station was cable-assisted, using power generated by a stationary steam engine at the top of the incline. ( Postcard published by the Locomotive Publishing Society Ltd., London. )

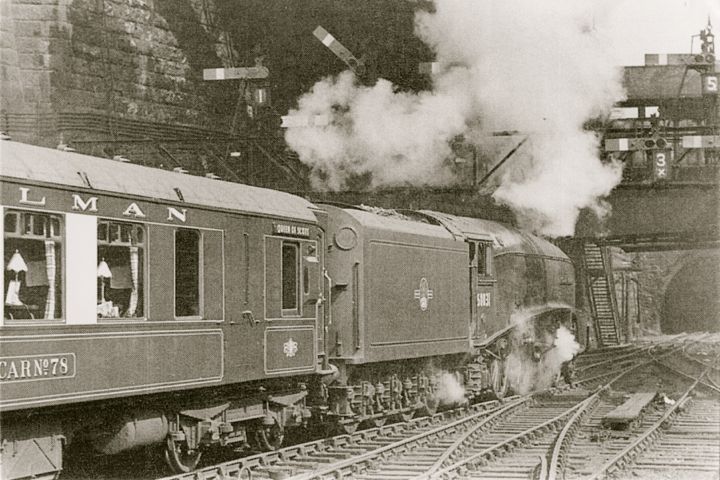

Departing Queen Street Station

Fast forward 60 years. It’s 11am and the “Queen of Scots” Pullman train is departing Glasgow Queen Street Station for London King’s Cross, calling at Edinburgh Waverley, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Darlington, Harrogate, and Leeds Central before arriving in London at 7.45pm. In this scene, the train is being hauled by the Gresley A4 Pacific locomotive 60031 Golden Plover. This was a sister locomotive to the Mallard, which had set a new record of 126 mph for steam locomotion on 3rd July, 1938, a record which still stands to this day. I actually witnessed the “Queen of Scots” departing Queen Street Station on three occasions and on one of them Golden Plover was the locomotive. Pullman coaches got their name from American George Pullman who, after spending an uncomfortable night sitting in a train traveling from Buffalo to Westfield in New York State, conceived of a railway carriage with luxurious appointments that could convert into a sleeping car for overnight travel. Pullman coaches of the type shown in this photograph did not convert into sleeping cars but were certainly luxuriously appointed.

Eastfield Engine Shed, Springburn

Glasgow Central Station Concourse

Glasgow Central Station Platform 2

It’s approaching 10am at Glasgow Central Station in the late 1950’s and the Royal Scot express passenger train is preparing to depart from Platform 2 for London Euston. For the first part of the journey, the train will be hauled by 46240 City of Coventry, a member of the Princess Coronation class and one of the most powerful passenger steam locomotives in service with British Railways. This class had been designed primarily to haul premier trains on the West Coast mainline between Glasgow and London, over Beattock Summit and Shap Fell. The express will make a brief stop at Carlisle to change engines and crews, before continuing on to London where it should arrive around 6pm.

Corkerhill Engine Shed, Mosspark

This shows a view of the former Glasgow & South-Western Railway engine shed at Corkerhill, near Mosspark, in 1954. Most of the locomotives in the picture would have worked goods or light passenger services except for the small tank engine in the middle, which would have fulfilled primarily shunting or station pilot duties. The mainline station serviced by Corkerhill passenger and express parcel locomotives was Glasgow St. Enoch Station.

{ 1 trackback }

{ 25 comments… read them below or add one }

Hello Chris,

Pen and Sword Books has a new title in the Regional Tramway series that I thought you might be interested in featuring on your website as a possible article: Regional Tramways – Scotland.

If you would like to receive a copy to review on your website, please don’t hesitate to let me know and I will have one sent out to you as soon as possible. Alternatively, have a look at our Transport category page on the website, I’m sure something there would be interesting to you!

I look forward to hearing from you,

Milly

Hello Milly,

Thank you very much for your very kind offer and I will be in touch via email. I wish you the best of success with your new publication.

Chris

I served my time as a boiler maker at Cowlairs locomotive works in 1943 then moved to Canada in 1951. I would like to hear from someone who remembers the old Cowlairs works.

Hi Chris,

Can you tell me if the Flying Scotsman travelled from London to Glasgow in the 1930’s, or was it the Mallard?

Margaret

Hello Margaret,

Thank you for your question. I think you are probably referring to the steam locomotive Flying Scotsman. There is also an express train by this name which is still running today, between London and Edinburgh. I don’t think it ever came through to Glasgow. You would have to change to another train. As for the steam locomotive Flying Scotsman, it was built in 1923 and became a flagship locomotive for the newly-formed London & North Eastern Railway (LNER). For part of its service, the locomotive Flying Scotsman was equipped with a corridor tender and assigned to the Flying Scotsman non-stop express, so I think it would have been restricted to this route and to depots in London and Edinburgh. Once it was taken off duty on the Flying Scotsman express and had its tender changed then it might have ended up in Glasgow on occasions.

With respect to the Mallard, it was built as a streamlined express locomotive in 1938 and soon thereafter broke the world speed record for steam locomotion, a record which still stands today. There were times when Mallard was not restricted to operations between London and Edinburgh, in which case it may also have appeared in Glasgow. I hope this helps.

Best wishes,

Chris

Hi Chris,

I’m in Canada and not familiar with Captcha. I have a Comment/Question that I’d like to leave.

Regards,

Ian Hay

Born Springburn; Railway Nut!

Hi Ray,

Captcha is just a check to make sure that you are a real person. Just enter the code and then you should be able to post your comment or question.

Thank you.

Chris

Hi Chris,

Great web site and history! I am doing some family history / genealogy research. Do you know which rail line would have run between Glasgow and Liverpool in the 1880’s? I am trying to figure out whether such a trip was done easily, if family would pop back and forth to visit, perhaps, or whether such a trip was a major investment in time and money. Was this a regular route? I have a mystery family member who had a photo taken in Birkenhead around 1880. She was born and raised in Glasgow and, to the best of our knowledge, never lived in Liverpool or Birkenhead. She did, however, have nieces and nephews who did at the time. Any thoughts? Thank you!

Kim

Hi Kim,

Thank you very much for your message and comments. In travelling from Glasgow to Liverpool or Birkenhead by train in the 1880’s, your ancestors would have probably have begun their journey at the recently completed Glasgow Central Station where they would board a Caledonian Railway express bound for Carlisle. On arrival at Carlisle Citadel Station, they would probably freshen up and take refreshment before boarding a London & North Western Railway (LNWR) express for Warrington or Crewe, and most likely stopping at Lancaster, Preston, and Wigan along the way. They would arrive at Warrington or Crewe late in the day and probably take accommodation for the night. Then the following day they would complete their journey to Liverpool, again via the LNWR. Once in Liverpool, they would have the option to take the steam ferry across the River Mersey to Birkenhead. In 1886, the Mersey Railway Tunnel opened so then they could also traverse the river by train.

In those days, travel by train took considerably longer than it does today and it was not just a matter of speed. In the 19th Century, railway carriages did not have corridors so passengers would not have access to a dining car or toilet while on board the train. They would have to wait until the train stopped at stations along the way and time was allowed for this. I hope this helps.

Best wishes,

Chris

Hi Chris,

I stumbled on this site by accident as I researched my Scottish ancestry.

My great-great-grandfather, Thomas Neil, living in Cowcaddens, Glasgow from the 1840’s to 1860’s, was an engine driver. In three census, marriage and birth (son’s) records he is listed as engineer apprentice, engineer, engine driver. Where and which rail company would he have likely worked for? What were the conditions like? Where can I find more information?

I live in Australia.

Regards, Margret

Hi Margret,

Thank you very much for your inquiry. In 1840, the railways and steam traction, having been developed in Great Britain, were still in their infancy, so your great-great-grandfather would have been getting in on the ground floor. I can only surmise where he found employment but it would most probably have been on the north side of Glasgow because he was living in Cowcaddens ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cowcaddens ). Perhaps the most likely opportunity would have been the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway which began carrying passengers on 21st February, 1842 between Edinburgh Haymarket Station and Glasgow Dundas Street Station ( subsequently renamed Queen Street Station ). ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edinburgh_and_Glasgow_Railway ). The engine shed and engineering works supporting this service at the Glasgow end were at Cowlairs, just north of Queen Street Station in the Springburn district (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cowlairs_railway_works). Your ancestor would probably have walked from Cowcaddens to Cowlairs, a distance of two miles or less across parts of open countryside. He could have started his training in the engineering shop at Cowlairs and later qualified to operate locomotives from the engine shed. The Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway was a very successful venture, almost doubling the original passenger estimates, so that by 1850 the company operated 58 locomotives. There would have been plenty of heavy engineering work for your great-great-grandfather.

With best wishes,

Chris

Dear Chris,

I hope you are safe and well.

Recently I found an account written by my grandmother of a trip from Glasgow to London in October 1910, when she was ten years old. The details of the journey are minimal:

“Mother and I arrived at Euston on Monday night 10 October…” and

“15 October 1910. Started off by 10 A.M. train for Glasgow”.

I have transcribed the story and I am researching the details and adding period photos where possible. Could you possibly help with some details of that trip?

I’m most grateful.

Kindest regards,

Matt

Dear Matt,

Thank you very much for your inquiry. By the time that your grandmother and great grandmother travelled between Glasgow and London in 1910 the railway systems in the Kingdom were well established, which is not surprising considering that they originated in Great Britain.

Your ancestors would have taken the same route to London as is in operation today, namely the West Coast Main Line (WCML). Here is a link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_Coast_Main_Line_diagram They would have begun their journey at the Caledonian Railway’s principal station, Glasgow Central, and boarded the Caledonian Railway express bound for Carlisle, passing through Motherwell, Carstairs, over Beattock Summit, past Lockerbie, across the Border at Gretna Green and into Carlisle. Then they would transfer to a London and Northwestern Railway (LNWR) express bound for London Euston. By 1910, this would have been timetabled to connect with the Scottish express trains. The route would include Penrith, Shap Fell, Lancaster, Preston, Wigan, Warrington, Crewe, Stafford, Nuneaton, Rugby, Bletchley, Watford, and eventually London Euston Station. It is difficult to gauge the total travel time in 1910 as there would have been stops along the way to pick up and drop off passengers as well as to change crews and locomotives. Also, banking engines may have been provided to transit Beattock Summit and certainly Shap Fell. If everything went according to plan and the Carlisle connection was good, the total journey time could have been less than 10 hours.

Long-distance trains in 1910 would have corridors, toilets and dining facilities so there was no longer the need to stop at stations so that passengers could purchase food and use the toilets.

I hope this helps.

With best wishes,

Chris

Hi Chris,

I wondered if you could help me figure out how I could find information about railway workers in Glasgow in 1951, I am trying to trace my mother-in-law’s real father, and all the information I have is that his name was George Reilly, he was a railway worker in Glasgow, and he was there in 1951. Any help would be appreciated.

Thanks in advance.

Carly

Hi Carly,

Thank you for your inquiry. It may be that George was employed on the railways before 1951 and possibly by one of the two companies that served Glasgow before British Railways was formed in 1948. These companies were the LMS ( London, Midland & Scottish Railway ) and the LNER ( London & North-Eastern Railway ). Employment records for these companies are held in the National Archive and they may also include early British Railways employment records. Here’s the link: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/railway-employment-records-1833-1956/ Hopefully, the people there should be able to help you.

Best wishes,

Chris

Hi Chris,

Great website – The railway family is a wonderful one, that stays with you your whole career, even after you’re no longer “officially” in it! And it looks like its charm is still working with future generations of railway people. A work pal of mine recently shared that his teenage son’s passion is diesel trains, and he’s hoping to become a Scotrail engineer when he leaves school. His bedroom is packed with train memorabilia (I have quickly turfed out my cupboard at work in his direction!) and his dad is on the hunt for logos from earlier incarnations of train graphics to add to the artwork on his wall (see pic)… If any railway colleagues can point me in the right direction or have any ideas for railway gifts for the lad who has everything (the train simulator tours don’t seem to be running anymore?) please feel free to shout! This is for a friend of a friend. Thanks

Abid

Hi Abid,

Thank you for sharing this and I agree with you about the railway family. My father, brother and several uncles were “on the Railways”. My father started out at age 16 in Crewe as a messenger boy on a bicycle, working for the London, Midland & Scottish Railway (LMS). He retired at age 60 as the British Railways Operating Superintendent for the West of Scotland.

Best wishes,

Chris

Hi Chris,

I was a fireman at Eastfield Traction Depot at Springburn in 1974 and my uncle, Jim Matthew, was a mainline driver at the same depot. He was an old steam locomotive driver and was originally at Dawsholm Shed, as was my grandfather. The picture of Eastfield Shed is fantastic and hadn’t changed that much since I worked there from 1974 onwards.

Derek

Hi Derek,

Thank you for sharing your family’s involvement with Glasgow’s Railways. In the days of steam, Eastfield would have been called an Engine Shed, and referred to as Eastfield Shed or just Eastfield.

It’s interesting that your father and grandfather both worked out of Dawsholm which housed some Stanier tank engines for service on suburban passenger routes. There were also some very powerful ex-War Department 2-8-0 locomotives based at Dawsholm that used to haul the heavy coal and iron ore trains. That must have been a sight to see.

All the best,

Chris

Hi Chris,

I’m trying to find out about a train which my great grandfather accompanied to Argentina or Brazil from Glasgow. This would have been around 1940 – 1950. He worked for the LNER.

I hope you can help.

Brian

Hi Chris,

I’m trying to retrace a journey made by a relative who eloped in March 1910. They left London on a Friday evening and boarded a ship in Glasgow the following day. Would there have been sleeper trains running on the West Coast Main Line at that time? Thanks.

Anna

Hi Brian,

Thank you for your inquiry and I think you may be referring to locomotives built in Glasgow for export that were accompanied by your great grandfather to a port in Argentina or Brazil.

On reviewing further, I think it’s quite likely that the ship was heading for the Argentine Capital of Buenos Aires on the Rio de la Plata, the River Plate. The early railways in Argentina and in neighboring Chile were British-owned and operated, so obviously they would order locomotives most likely built in Glasgow. I hope this helps.

Best wishes,

Chris

Hello Anna,

Thank you very much for your inquiry. At the time of the elopement in 1910, the railways in Great Britain were well-established and services in different regions were operated by different private companies, the largest of which was the London & North Western Railway Company ( LNWR ). This serviced routes between London Euston Station and the cities of Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester and Carlisle. If the train was destined for Glasgow then the LNWR locomotive would be uncoupled from the train at Carlisle Citadel Station and replaced with a Caledonian Railway locomotive which would then continue the journey north to Glasgow Central Station. Night trains certainly operated at that time and they probably included sleeping cars.

Fortunately, if you would like further information such as the timetabling and presence of sleeping cars in 1910, there is actually a London & North Western Railway Society. They have a website, https://lnwrs.org.uk which you can view and then contact them for further details.

I hope this helps.

Best wishes,

Chris

Hi Chris.

I have an ebony wood walking cane with a silver engraved cap and silver end which was presented to my uncle in 1926. The inscription reads “Presented to Mr Donaldson by St Rollox YUA 1-1-26”. Would you happen to know what the YUA stands for? I think it might have been an association or club.

Thank you.

Kenny

Hi Kenny,

Thank you for your inquiry. I’m assuming that your uncle retired after many years service at the St. Rollox Works in Springburn where locomotives and rolling stock were manufactured and serviced. He probably joined when the Works were owned and operated by the Caledonian Railway and then, when he retired, they would have been under the auspices of the LMS, the London Midland & Scottish Railway. So far, I have not been able to find any mention of a YUA which, I agree, could be association. If you have access to any of your uncle’s letters or papers, they may provide a clue.

With best wishes,

Chris